A blog about liberal Christianity, Quakerism, systems thinking, information, social justice and queer rights. May contain sermons.

Saturday, 10 April 2021

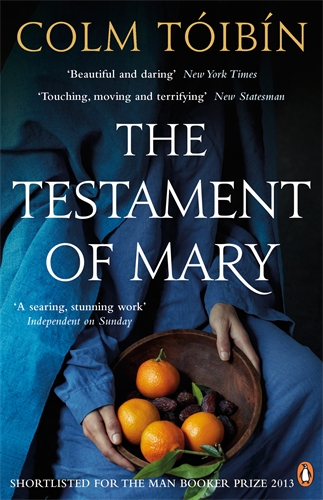

On hunting and being hunted: the role of narrative in The Testament of Mary

Sunday, 14 February 2021

On being a nomad: multiple experiences of spiritual community

(I think that 'words that I might have offered in ministry but didn't quite feel appropriate' must be a distinctive Quaker literary form. Here is one such.)

This morning in Meeting for Worship we were reminded of the words of Caroline Stephen, written in 1908, that "the presence of fellow-worshippers in some gently penetrating manner reveals to the spirit something of the divine presence" (Quaker Faith & Practice 2.39). So I spent much of the meeting thinking about my experience of spiritual community.

|

| Image: Jewish Journal |

I've recently been reading a recent wonderful collection of short articles on sexuality and religion, The Book of Queer Prophets (ed. Ruth Hunt), appropriate for LGBT History Month. Among many lovely pieces is one by Padraig O'Tuama, who writes among other things about community among LGBT people and compares their (and his) experience to that of the Israelites being persecuted in Egypt, and the way that persecution shaped their community. He writes: "A people became a people because of their shared need to move out from a system that abhorred them. ... 'Let my people go', someone said to a person in power, and those under the power realised they were a people."

That experience of being persecuted for one's difference, and then that persecution leading to the formation of community, is one that many groups have found around the world. Some scholars suggest that the ancient Israelites were not a single ethnic group (notwithstanding the origin story of Jacob and Joseph in the book of Genesis), but rather were a disparate group who formed around their slavery, escape from Egypt, and journeys in the wilderness. The story of gay men finding a common identity through persecution and death in the 1980s is told beautifully in the recent TV series It's a Sin. Successive generations of African-Americans have built supportive community in the face of white supremacy and found ways to fight for justice (during slavery, the Jim Crow period in the southern states, in the Civil Rights movement, and more recently in Black Lives Matter). And Quakers too formed and were shaped through persecution, in the early decades of their movement when their theological and political radicalism was so threatening to the state that many were imprisoned and sometimes Quaker meetings were kept alive by their children.

For myself, my life experience haven't led to that sort of persecution or that sort of community. I'm white and middle-class. I've never been persecuted for my faith, whether as a Quaker or as a liberal/progressive participant in Presbyterian churches (I've occasionally been accused of not being a true Christian by evangelicals, and even left one church when it became too evangelical, but that's hardly persecution). And while I've been on the fringes of the LGBT community for many years, I've largely been sufficiently straight-acting not to attract hostility from anyone.

And yet I found myself realising that I have a deep yearning and need for spiritual community, to join with others to explore what it means to be in relationship with God, what it means to be human, what it means to seek after truth, what it means to have love for others, what it means to live in harmony with the natural world, what it means to seek justice.

I've found some of that sense of spiritual community through Quaker meeting, sometimes through local meetings (I've been a close part of at least eight local meetings, though none for more than a few years as life took me to different places) but just as much through national Quaker groups. I've found some of it through churches in the United Reformed Church and the Church of Scotland (again at least four of those, but more loosely with a number of other churches where I've preached). I've found it through the Iona Community, in Glasgow and on Iona but just as much in our local and regional groupings; and by attending the Greenbelt festival for a decade. I've found it through conversations with family and friends. And in a way I've found it through a community of ideas around progressive Christianity, in books and podcasts where I'm more of a recipient than a generator of ideas, but of which I certainly feel a part and which inform some of the other spaces.

This long and disparate list of spiritual communities shows the difficulty in some ways of my spiritual journeys - I've very much been a nomad rather than a settler, and even though many of the ideas and experiences have a lot in common, the people and the groupings are quite distinct. I've had a deep sense of connection with many people through these communities, but not always for very long. This is a very different experience both from the person who's been part of a single spiritual community (such as a church) for many years, and it's also very different from the people I discussed above who have been joined together in community through persecution. My experience is richer for perhaps being quite broad, but poorer for perhaps being more more shallow. There's a lot more 'I' in this piece than 'we'. Sometimes I feel that I would like to settle in a single spiritual community. Sometimes I've felt that I had found one, and then life changed in various ways.

And maybe this nomad form of community is its own form of spiritual experience, as I've met and encountered others with the same pattern from time to time, who find their way through travelling rather than arriving. In a hymn by Joy Dine that has spoken to me for some years are the words: "When we set up camp and settle / to avoid love’s risk and pain / you disturb complacent comfort / pull the tent pegs up again". Perhaps there is calling in this way of peripatetic spirituality. But I do value depth in community as well as breadth. So my own search for community continues.

Wednesday, 13 January 2021

Life in the midst of death

| Image: American Society for Cybernetics |

Walking through the woods, I am reminded that there is as much death here as life. It is a mistake to think the word forest refers only to the living, for equally it refers to the incessant dying. It is mistake to speak of preserving forests as preventing the death of trees. Forests live out of the deaths of toppled giants across the decades, as well as the incessant dying of microscopic being. Without death, the forest would die. Ultimately, it is only the removal of trees that can deplete the forest. ... Death is apparently not a failure of life, but a mode of functioning as intrinsic to life as reproduction. To see life without seeing death is like believing that the earth is flat and matter solid - a convenient blindness.

death is a very important part of life that we shouldn’t deny, that in spite of our terrible hubris and greed and competitiveness, that we can learn to see ourselves in proportion and realize that we’re small and temporary and don’t understand as much as we need to. And we live in a time of real urgency, where we have to mine the insights of the past.

Mary Catherine Bateson wrote extensively about life - perhaps her most widely-read book (and the theme of the much of the On Being interview) was entitled Composing a Life, on how we learn to live as a form of improvisation, and progressively find meaning in our lives as we go. Eventually life ends, but that brings me to one last piece of her wisdom from her memoir of her parents, With a Daughter's Eye, p.269 (thanks to my colleague Kevin Collins for finding the reference - there's a searchable version on Amazon):

The timing of death, like the ending of a story, gives a changed meaning to what preceded it.

I appreciate that wisdom as a historian of people with ideas, whose ideas can only really be understood once we them in full after their death (and sadly I've often understood systems thinkers best through their obituary and memorial articles in journals). But I also appreciate that wisdom as a person, still coming to terms with the death of my father just over a year ago, as we all need to take time to reflect on the lives of those we have known and those we have loved. Even if their stories have ended, our reading of those stories goes on for a long time to come.

In the midst of life, we are in death. But hope can be found in life, and hope can be found after death.

Change anxiety

Today in Quaker Meeting for Worship, some ministry came to me, around change in the world and my associated anxiety. After some deliberation...

-

The song "Jonah and the Whale" is much beloved at Sunday Schools . It's jolly but (like lots of Sunday School versions of the ...

-

Sermon preached at Duston URC , 11 March 2018. Texts: Numbers 21:4-9 and John 3:14-21 . Image: imgflip.com A couple of months ago, my...

-

[Sermon preached at Duston United Reformed Church, 30th March 2014, Mother's Day. Text: Luke 1:46-55 , The Magnificat. The sermon was im...