Sermon preached at Abington Avenue United Reformed Church, on 27th September 2015. Texts: Exodus 20:1-6 and Luke 12:32-34.

Who is your god? Who do you worship on a daily basis? Here is what the Nicene Creed, recited weekly in many churches, says:

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is, seen and unseen.

We don’t use many creeds as such in the United Reformed Church, but the closest thing we have is the Nature, Faith and Order of the URC, which I last heard in this building at Jane’s induction service – it’s kept for special occasions. That says:

With the whole Christian ChurchSo that’s that. We believe in one God. The writers of Exodus would be pleased. Sermon over, amen. Or perhaps not.

the United Reformed Church believes in one God,

Father Son and Holy Spirit.

The living God, the only God, ever to be praised.

Because do we really believe in one God? Do we really put our total faith in the Triune God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit? Because here’s the thing about faith – it’s not about words. Saying the right prayers doesn’t make you a Christian. Believing the right things doesn’t make you a Christian. What makes you a Christian is the way you live your live, the relationship you have with God and with Jesus, and the effect that has upon you every single day. Of course this is the case in most other faiths as well – being a good Muslim is about the way you pray, the things you do; likewise for being a good Buddhist or Hindu or Sikh. And it’s been the case in the Jewish faith since the words we’ve heard today were given to Moses, and remains the case to the present day. Faith is not about doctrine. It’s about a lived experience of the divine in everyday life.

So the question becomes, who are our gods? Who are the idols that we put before the one true and living God? Not in our beliefs perhaps, not in the prayers we say, but in our everyday lives?

Let me start with a story of a fairly trivial example of idol worship from my own life. Are there any children present? [Nope, good.] Because I need to tell you about my idolatrous worship of Santa Claus. Now, I don’t believe in the fellow and we've struggled with wanting to be honest with our children while also keeping Christmas fun for them. So of course we do the usual things – get the kids to leave out stockings, we fill them in the night. So last Christmas Eve we filled the stockings, and then I ate half a mince pie and half a carrot. And then went to a midnight service. Now who was I worshipping in that moment? Because whatever I might believe about Santa, I was sure acting as though I believed in him.

Trivial example, you might say. The things we do for our children. Nobody really believes in Santa. But there are older gods. In ancient times they had names like Aphrodite, goddess of love and sex; or Mammon, the god of money; or Mars, the god of war and violence. And nobody uses those names any more, but many many people worship those gods through their everyday actions. Many of us here, at some point in our lives, has had one of those trio completing dominating our lives to the exclusion of everything else. Or if you’ve not been tempted by sex, money or war, how about one of the following gods: consumerism, the worship of possessions, the greedy grasping for more stuff; or work, undoubtedly a gift and also necessary to keep food on the table, but almost an addiction for so many people; or power and status and fame - seeking those completely dominate some people’s lives.

Now I’m not saying most of these things are wrong by themselves. Love, money, work, nice objects, recognition for your service to others – these are all important things. In their different ways, they are gifts from our true God. But when they become the centre of our lives by themselves, when we become separated from a relationship with the divine presence that created, redeemed and sustains the universe – then love, money, work and the rest become idols. The theologian Tom Wright has written at length on this subject. Here’s what he says:

|

| Mammon worship, painting by Evelyn De Morgan (1909) |

Worshipping them demands sacrifices, and those sacrifices are often human. How many million children, born or indeed unborn, have been sacrificed on the altar of Aphrodite, denied a secure upbringing because the demands of erotic desire keep one or both parents on the move? How many million lives have been blighted by money, whether by not having it or, worse, by having too much of it? And how many are being torn apart, as we speak, by the incessant demands of power, violence, and war?And he’s right. Take consumerism, that most modern of God's, the urge to buy more. We live in a throwaway society. We are surrounded by plastic packaging, irrelevant bits of tat that amuse us for seconds and then get thrown away, technology which was the latest thing last year but now is so passé that if it’s lucky it gets sent to some forgotten corner of Asia for recycling, otherwise into the landfill. And at each stage, the planet’s resources are consumed, people’s lives are blighted in seeking out the rare minerals and the oil, pollution and waste are increased. And here of course we go into debt to afford the stuff, we worry and some people are destroyed by it. Everywhere, people are being sacrificed on the altar of the false god called consumerism. And we’re told it makes us good citizens, it contributes to the economic recovery, it satisfies the market. Buy more things, it'll make you happy. And yes it can, briefly. But at such cost.

I’m not saying this with any self-righteous. I’m a slave to the worship of consumerism like so many of us. I like shiny pretty things, new technology and the like. I buy my children rubbish plastic tat which lasts for five minutes, or let them spend their money on it. In our society it’s really difficult not to worship that particular god.

And of course you could say the same thing for all the false gods, all the idols we put in front of the one true God. They all promise excitement, satisfaction, but the things they give us are transitory, fleeting, gone in a moment – and they bring suffering in their wake, across the globe. People follow them because they promise happiness, but all they do is stand between us and our God.

Now this is all sounding a wee bit doom and gloom. Is there no hope? Because it’s pretty hard to resist the pull of money, and consumerism, and power and the rest. But I want to go back to the Exodus reading and see the sign of hope in it right at the start. Verse 1 reads: “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery”. That’s the thing that comes first, before we get into the teaching on worshipping no other gods, and then on the rest of the Ten Commandments that follow the short passage we heard.

But that coming out of slavery, that’s absolutely crucial to why the Ten Commandments were given to the people of Israel. They’d spent hundreds of years as slaves in Egypt. They weren’t free to live their own lives as they pleased. They were mistreated, humiliated, treated as sub-human. Slavery is an awful institution. And it’s absolutely central to the way the Jewish people saw themselves in the time of Moses, and in the time of Jesus, and to the present day. They were the people who were enslaved, they are now the people who are free. And they were set free by this God of theirs. So the Ten Commandments aren’t about restriction and rule, they’re a bold statement to a people previously crushed down by slavery that this is what freedom looks like, this is what it means to be a free people.

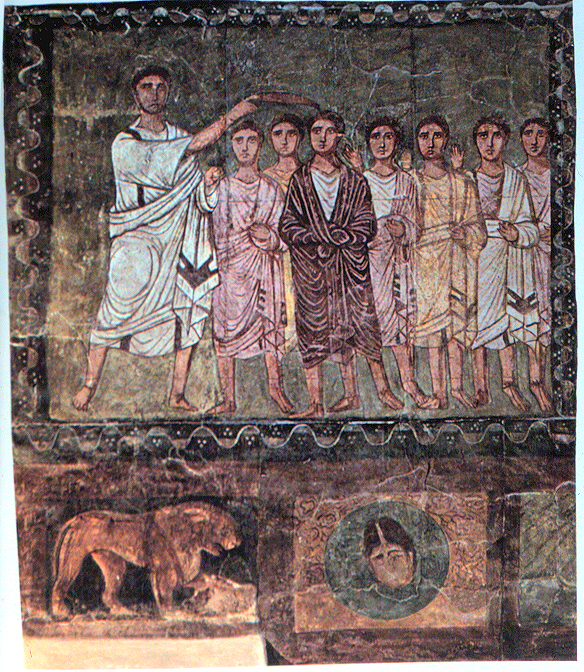

And it begins with a relationship with God. With their God, the one who freed them. The one who had the power and the love to free them from their slavery. The Israelites of that time believed in the existence of other gods, and saw plenty of them in Egypt and later in Canaan. The Old Testament is chock-full of other gods, other powerful figures, as well as Yahweh. To call these people monotheists is misleading. But they only had a relationship with this one god, with the one who had been the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; but now, more importantly, was the one who had freed them from slavery. It’s said that in the Old Testament, God is referred to as the creator 6 times, but as the one who freed them from slavery 36 times.

And by worshipping their god, and setting aside idols, they were able to remain as free people in their hearts as well as in the literal sense. They weren’t going to be drawn into their own slavery. They weren’t very good at it. The Old Testament is the story of how difficult the people of Israel found it to resist worshipping idols. Sometimes they bowed down before graven images, as Moses found when he came down the mountain. Sometimes they became the enslavers themselves, as in the time of Solomon. Often they took power and war as their idols. The prophets came and warned them of this. And progressively, insidiously, the law itself became an idol, the Torah that began as the sign of their freedom.

And by worshipping their god, and setting aside idols, they were able to remain as free people in their hearts as well as in the literal sense. They weren’t going to be drawn into their own slavery. They weren’t very good at it. The Old Testament is the story of how difficult the people of Israel found it to resist worshipping idols. Sometimes they bowed down before graven images, as Moses found when he came down the mountain. Sometimes they became the enslavers themselves, as in the time of Solomon. Often they took power and war as their idols. The prophets came and warned them of this. And progressively, insidiously, the law itself became an idol, the Torah that began as the sign of their freedom. And of course that was one of the main messages Jesus came to give the people of Israel. Don’t get trapped by your laws. The Sabbath was made for people, not people for the Sabbath. He didn’t come to destroy the Torah but he did come to fulfil it and allow the Israelites not to be trapped by it, to free them from their slavery to law.

And Jesus promises us the same freedom. The whole Torah could be summed up by two commandments, he said. The first was the great prayer of the Jewish people, the Shema, with which we began the service – “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind”. And the second, he said, is like it: “Love your neighbour as yourself”. [Matt 22:37-39, NIV]

That’s it. That’s how we can be freed from the idols, the false Gods which dominate our lives. By loving God with everything we have. By loving our neighbour. By living out our lives in accordance with the lines in the first letter of John:

We love because he first loved us. Whoever claims to love God yet hates a brother or sister is a liar. For whoever does not love their brother and sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen. (1 John 4:19-20, NIV)The question really is what you put at the centre of your being. Jesus put it so succinctly, in the final verse that we heard: “where your treasure is, there your heart will be also”. By following the way of love, for God and for all people, we cast aside the worship of false gods and idols, and we gain freedom in all our lives. God be thanked. Amen.