A blog about liberal Christianity, Quakerism, systems thinking, information, social justice and queer rights. May contain sermons.

Saturday, 10 April 2021

On hunting and being hunted: the role of narrative in The Testament of Mary

Sunday, 14 February 2021

On being a nomad: multiple experiences of spiritual community

(I think that 'words that I might have offered in ministry but didn't quite feel appropriate' must be a distinctive Quaker literary form. Here is one such.)

This morning in Meeting for Worship we were reminded of the words of Caroline Stephen, written in 1908, that "the presence of fellow-worshippers in some gently penetrating manner reveals to the spirit something of the divine presence" (Quaker Faith & Practice 2.39). So I spent much of the meeting thinking about my experience of spiritual community.

|

| Image: Jewish Journal |

I've recently been reading a recent wonderful collection of short articles on sexuality and religion, The Book of Queer Prophets (ed. Ruth Hunt), appropriate for LGBT History Month. Among many lovely pieces is one by Padraig O'Tuama, who writes among other things about community among LGBT people and compares their (and his) experience to that of the Israelites being persecuted in Egypt, and the way that persecution shaped their community. He writes: "A people became a people because of their shared need to move out from a system that abhorred them. ... 'Let my people go', someone said to a person in power, and those under the power realised they were a people."

That experience of being persecuted for one's difference, and then that persecution leading to the formation of community, is one that many groups have found around the world. Some scholars suggest that the ancient Israelites were not a single ethnic group (notwithstanding the origin story of Jacob and Joseph in the book of Genesis), but rather were a disparate group who formed around their slavery, escape from Egypt, and journeys in the wilderness. The story of gay men finding a common identity through persecution and death in the 1980s is told beautifully in the recent TV series It's a Sin. Successive generations of African-Americans have built supportive community in the face of white supremacy and found ways to fight for justice (during slavery, the Jim Crow period in the southern states, in the Civil Rights movement, and more recently in Black Lives Matter). And Quakers too formed and were shaped through persecution, in the early decades of their movement when their theological and political radicalism was so threatening to the state that many were imprisoned and sometimes Quaker meetings were kept alive by their children.

For myself, my life experience haven't led to that sort of persecution or that sort of community. I'm white and middle-class. I've never been persecuted for my faith, whether as a Quaker or as a liberal/progressive participant in Presbyterian churches (I've occasionally been accused of not being a true Christian by evangelicals, and even left one church when it became too evangelical, but that's hardly persecution). And while I've been on the fringes of the LGBT community for many years, I've largely been sufficiently straight-acting not to attract hostility from anyone.

And yet I found myself realising that I have a deep yearning and need for spiritual community, to join with others to explore what it means to be in relationship with God, what it means to be human, what it means to seek after truth, what it means to have love for others, what it means to live in harmony with the natural world, what it means to seek justice.

I've found some of that sense of spiritual community through Quaker meeting, sometimes through local meetings (I've been a close part of at least eight local meetings, though none for more than a few years as life took me to different places) but just as much through national Quaker groups. I've found some of it through churches in the United Reformed Church and the Church of Scotland (again at least four of those, but more loosely with a number of other churches where I've preached). I've found it through the Iona Community, in Glasgow and on Iona but just as much in our local and regional groupings; and by attending the Greenbelt festival for a decade. I've found it through conversations with family and friends. And in a way I've found it through a community of ideas around progressive Christianity, in books and podcasts where I'm more of a recipient than a generator of ideas, but of which I certainly feel a part and which inform some of the other spaces.

This long and disparate list of spiritual communities shows the difficulty in some ways of my spiritual journeys - I've very much been a nomad rather than a settler, and even though many of the ideas and experiences have a lot in common, the people and the groupings are quite distinct. I've had a deep sense of connection with many people through these communities, but not always for very long. This is a very different experience both from the person who's been part of a single spiritual community (such as a church) for many years, and it's also very different from the people I discussed above who have been joined together in community through persecution. My experience is richer for perhaps being quite broad, but poorer for perhaps being more more shallow. There's a lot more 'I' in this piece than 'we'. Sometimes I feel that I would like to settle in a single spiritual community. Sometimes I've felt that I had found one, and then life changed in various ways.

And maybe this nomad form of community is its own form of spiritual experience, as I've met and encountered others with the same pattern from time to time, who find their way through travelling rather than arriving. In a hymn by Joy Dine that has spoken to me for some years are the words: "When we set up camp and settle / to avoid love’s risk and pain / you disturb complacent comfort / pull the tent pegs up again". Perhaps there is calling in this way of peripatetic spirituality. But I do value depth in community as well as breadth. So my own search for community continues.

Wednesday, 13 January 2021

Life in the midst of death

|

| Image: American Society for Cybernetics |

Walking through the woods, I am reminded that there is as much death here as life. It is a mistake to think the word forest refers only to the living, for equally it refers to the incessant dying. It is mistake to speak of preserving forests as preventing the death of trees. Forests live out of the deaths of toppled giants across the decades, as well as the incessant dying of microscopic being. Without death, the forest would die. Ultimately, it is only the removal of trees that can deplete the forest. ... Death is apparently not a failure of life, but a mode of functioning as intrinsic to life as reproduction. To see life without seeing death is like believing that the earth is flat and matter solid - a convenient blindness.

death is a very important part of life that we shouldn’t deny, that in spite of our terrible hubris and greed and competitiveness, that we can learn to see ourselves in proportion and realize that we’re small and temporary and don’t understand as much as we need to. And we live in a time of real urgency, where we have to mine the insights of the past.

Mary Catherine Bateson wrote extensively about life - perhaps her most widely-read book (and the theme of the much of the On Being interview) was entitled Composing a Life, on how we learn to live as a form of improvisation, and progressively find meaning in our lives as we go. Eventually life ends, but that brings me to one last piece of her wisdom from her memoir of her parents, With a Daughter's Eye, p.269 (thanks to my colleague Kevin Collins for finding the reference - there's a searchable version on Amazon):

The timing of death, like the ending of a story, gives a changed meaning to what preceded it.

I appreciate that wisdom as a historian of people with ideas, whose ideas can only really be understood once we them in full after their death (and sadly I've often understood systems thinkers best through their obituary and memorial articles in journals). But I also appreciate that wisdom as a person, still coming to terms with the death of my father just over a year ago, as we all need to take time to reflect on the lives of those we have known and those we have loved. Even if their stories have ended, our reading of those stories goes on for a long time to come.

In the midst of life, we are in death. But hope can be found in life, and hope can be found after death.

Sunday, 11 October 2020

All are welcome at the feast: a sermon on food and inclusion

Sermon preached at Duston United Reformed Church on 11th October 2020. Texts: Isaiah 25:4-8; Luke 14:15-24.

All the passages we’ve heard today – from Psalm 23, from Isaiah, and from Luke – are to do with feasting. The word feast is perhaps a little old-fashioned now. It conjures up images of Oxford colleges or medieval banquets, it belongs to the world of Henry VIII or Hogwarts. Indeed, there are many memorable feasts in the Harry Potter books. Here’s how JK Rowling writes about the first one that Harry encounters, fresh from his unhappy cupboard under the stairs:

"Harry’s mouth fell open. The dishes in front of him were now piled with food. He had never seen so many things he liked to eat on one table: roast beef, roast chicken, pork chops and lamb chops, sausages, bacon and steak, boiled potatoes, roast potatoes, chips, Yorkshire pudding, peas, carrots, gravy, ketchup and, for some strange reason, mint humbugs."Harry’s reaction is an important one, because although he was never starved at his terrible aunt and uncle’s house, he never had quite enough and never got the nicest things. In the same way, in a poor society where people are just scraping by, feasting on special occasions, every now and then, becomes really important. It’s a time to put away your everyday poverty and go wild for a brief time.

|

| Image: The Peasant Wedding by Pieter Brueghel, via Psephizo.com |

Let’s talk about food poverty in the world today for a moment, to put this in context. According to the most recent estimates, more than 800 million people across the world, roughly 1 in 9 of the world’s population, are undernourished – they don’t have enough food to live a normal active everyday life. This figure had been declining as a result of many international efforts, but it’s started to rise again in the past few years.

As you might have heard, the United Nations’ World Food Programme has just been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. They give direct assistance to the very poorest people in the world, more than 100 million people, and their work has been all the more important during the coronavirus pandemic. Food and hunger really matter. The World Food Programme’s director, David Beazley, said the following after the announcement of the prize:

"Where there is conflict, there is hunger. And where there is hunger, there is often conflict. Today is a reminder that food security, peace and stability go together. Without peace, we cannot achieve our global goal of zero hunger; and while there is hunger, we will never have a peaceful world."

Nor is this just a problem of so-called less developed countries elsewhere in the world. In our own rich country, according to Oxfam, more than two million people are undernourished, and half a million people are reliant on food parcels. This is a national and a global scandal. Helping individuals such as happens here with the food bank is really important, but ultimately we need deep changes to the systems which allow so many people to go hungry.

Returning to the world of ancient Israel, they lived in an agricultural society where many people were only one harvest away from starvation. The wider middle eastern area from Iraq to Egypt, including Israel, was known as the Fertile Crescent for its benign climate for growing crops, compared to many other areas, but there were frequent famines and disasters. In that world, feasting took on a deeper symbolism. It was a rare and special event. You couldn’t rely on it, and it felt like a gift from God.

As a result, many societies have ritualised such feasts, built them into religious traditions of all sorts, and ancient Israel had plenty of those. It also had a deeper significance, in that feasting was a key image of what they looked forward to when God brought about a better world in the future, in the end times. Thus the prophets are full of accounts of the future time when God will make a great feast, a banquet of rich foods and fine wines, in the way that we saw from Isaiah. There’s no sense of this being a different place – this is a new earth rather than heaven – but it’s a world transformed, a world of justice and peace, a world where everyone is welcome and everyone is fed.

And it’s that sort of feast that Jesus was talking about in his parable of the great banquet. It’s quite a complex story, of people being invited and refusing and then others put in their place. I have to confess that I’m not using the version of the parable that’s in the lectionary for today. We should be hearing the parable from the gospel of Matthew, which tells roughly the same story but adds layers of violence, exclusion and pretty blatant anti-semitism. Luke’s version is neater, has fewer layers, and is a lot less problematic. But there’s still a lot going on.

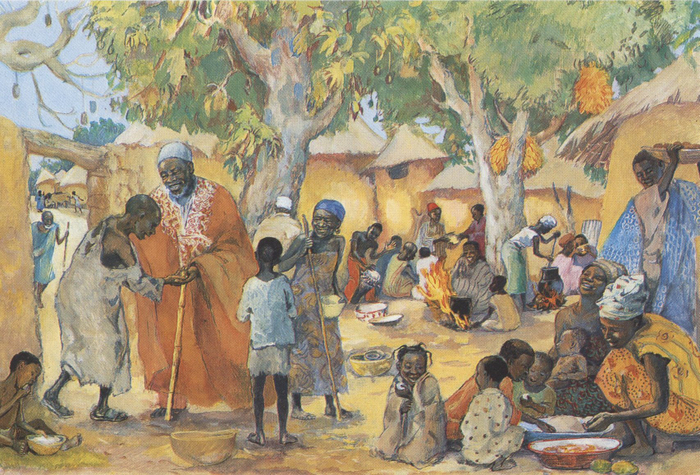

|

| Image: Jesus Mafa, via Vanderbilt University |

Now it’s not obvious from the text, but invitations in the time of Jesus were quite unlike in our time. Today when you’re invited to a dinner or a celebration, you’re told the time and place. In Jesus’ time, the guests were invited well in advance, agreed to come, and only later would they be told when the celebration was actually happening. So those excuses are partly because something else had come up in the mean time, those people who’d bought land or oxen, or who’d just got married. They’re partly to do with the time that had elapsed between the initial invitation and getting the details. I’ve done that myself at work – said I was free for a meeting on a range of dates, then had some of those dates fill up. It’s not necessarily that you don’t want to make the date, but it’s certainly a matter of priorities. The people invited simply don’t find the dinner as important as the other things they’ve got on. Now this parable has often been read allegorically, with lots of different groups reckoned to be the various people who reject the invitation, but I suggest that a simpler reading is easier: some people were invited to the feast, but they couldn’t make it any more because they had more important things to do.

And understandably, this would be pretty hurtful to the person giving the feast. They’d put in lots of effort and money planning this feast, and their guests don’t want to come. That’s a pretty horrible feeling. I’ve organised various events, in churches or at work or socially, and the start time was approaching, and people weren’t turning up, and my heart began to sink.

So I can readily imagine how the organiser of the feast might have felt by all those rejections. I think we can assume that he was a person of some high standing, so that all those rejections would have impacted on his social status as well, made him look less important.

He begins to sound pretty angry about the whole thing. “Go out at once into the streets and lanes of the town and bring in the poor, the crippled, the blind, and the lame” and then later when that’s not enough, “Go out into the roads and lanes, and compel people to come in, so that my house may be filled”. There’s a fair amount of grumpiness in that, but also a great deal of generosity. If we reckon that this man is rich, and was expecting lots of important guests at the feast, then it’s quite a shift to bring in the poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame. In a typical large social event of the time, those are the people who’d be at the far end of the table from the host, perhaps with less good food, if they got an invitation at all. But immediately before this parable, Jesus instructs those holding a feast to invite the poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame rather than relatives or rich neighbours, as those people can’t repay you through a return invitation. And the treatment of people like these who the Hebrew prophets constantly held up as the example of justice in society – doing God’s work is to care for widows, orphans, refugees and the disabled. It turns a typical middle eastern banquet for the privileged into what one commentator, Leith Fisher, called “the rugged folk’s banquet”.

|

| Image: The Additional Needs Blogfather |

So I think this parable is a call to generosity for those who have power and money and privilege, both individuals and society, to consider first those people who are disadvantaged. Stronger than that, it’s a statement that this is the way of the kingdom of God, to welcome all and to include all. The kingdom of God upends the structures of society. The rich, the leaders, the privileged in private jets and expensive houses – they come last; the poor, the downtrodden, the marginalised – they come first in God’s kingdom.

It’s a call to the church as well, to be a place of inclusion rather than exclusion. The hymn we heard before the sermon says that ‘all are welcome in this place’. It’s so wrong, indeed it’s breaking the clear word of Jesus in this parable, when churches turn away from their doors those who are disabled, or young children, or old people, or gay people, or people with autism, or transgender people, or people who don’t live locally, or people who aren’t enough like those in the existing congregation. The last hymn we’ll hear today begins “come all you vagabonds, come all you ‘don’t belongs’” and it was written based on this parable. Because that’s what the church is, or at least that’s what the church should be – the home of those who don’t belong, the home of the marginalised and the excluded.

And to me that’s a message of great hope. Because these are really rubbish times for a lot of people, but in those times that signs of hope are needed, and where messages like the feasts shown by Isaiah and by Jesus are so important. But they say: if you’re marginalised, if you’re on the edge of society in whatever way – then YOU are welcome at the table of the Lord. YOU are the invited guest at the great banquet. And YOU are beloved by God, in this time and in the world to come.

Amen.

Sunday, 13 September 2020

Forgiving others, as we are forgiven

Sermon preached at Duston United Reformed Church, 13/9/2020. Text: Matthew 18:21-35.

In the past couple of months, we’ve been mildly obsessed as a family with the musical Hamilton, the big-ticket show in New York and London which was released in a filmed version on Disney Plus this summer. We’ve watched it three times and listened many times to the music. For those who don’t know, it’s a mostly historically accurate portrayal of Alexander Hamilton, a key figure in the American revolution and the founding of the United States as an independent nation. It’s full of brilliant music and lyrics, and some very powerful moments. One of the most emotional scenes is concerned with forgiveness, so it’s directly relevant to this passage.In a terrible series of events, Hamilton had an affair when he was a prominent politician and his wife Eliza was away. He was subsequently blackmailed by the husband of the woman he’d had the affair with, which for complicated reasons left him open to charges of public embezzlement. To clear his name of those charges, he wrote a public pamphlet confessing to the affair, ruining his reputation and breaking his wife’s heart. His young adult son was then killed in a duel defending Hamilton’s honour, leading to a huge rift between Hamilton and Eliza.

In a beautiful song, Eliza burns all of Hamilton’s letters, writing herself out of his future narrative. And then they move together to a quiet part of New York, where they grieve and Hamilton sings how sorry he is, and where eventually Eliza is able to forgive him – and as Hamilton weeps, the chorus sing the word “forgiveness” over and over again. Another character refers to Eliza’s forgiveness as “a grace too powerful to name”.

Because that’s the thing about forgiveness. It’s really hard - really really hard. It takes time and it takes real work to forgive someone who’s done you wrong. Seventy-seven times, or seven times seventy times, as Jesus puts it. And for the one that gets forgiven, it’s experienced as an act of supreme grace.Forgiveness is a central theme in Jesus’ ministry, from start to end. He came proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. When he healed, he often told people that their sins were forgiven. And as he died, according to the gospel of Luke, he said “Father forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing”.

Jesus also taught about forgiveness in two important places in Matthew’s gospel. This is one, but the other we’ve spoken already in this service – the Lord’s Prayer, where he said the disciples should pray “forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us” ['forgive us our debts' in the Gospel], or “trespasses” as it’s often prayed in English churches, and went on after the prayer to say: “For if you forgive other people when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive others their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins”. That’s his only commentary on the Lord’s Prayer – forgiveness is literally the most important part of the prayer according to Jesus.

|

| The Unforgiving Servant by James Janknegt |

And so to the parable. It’s really quite complicated with its different servants. First thing to say is that it’s full of hyperbole, with details that are made deliberately stronger than they need to be. The amount the first servant is said to owe is so large to be impossible – in our money today it would be perhaps £4 billion. That’s the national debt of a small country. But it shows the sort of person the servant would have to be – someone huge and powerful in a life of the kind of hierarchical society pictured in the parable. That would make him a great lord, owing many obligations to his king but in turn owed many obligations by those in the many layers of the pyramid beneath him. And if the king forgave the debts of someone at the top of the pyramid, all the people below him also had their debts forgiven. So in refusing to forgive this much smaller debt – roughly worth £7000 in today’s money – the rich servant was not being mean and selfish, he was actively going against the whole point of forgiveness. By having his own debts forgiven, he was supposed to have forgiven those of others; he was breaking the rules, not passing on the good thing he had received. And debt is precisely the word found in the Lord’s Prayer, still said in Scotland as “forgive us our debts”, but as sins or trespasses here.

And it’s not hard to see why Jesus tells this story, why he links it to the life of the church community. Because forgiveness really matters in keeping any sort of community going. Consider conflict within churches. Conflict can simmer and remain around for many years, because people stay in the same churches for many years, even sometimes generations. I was part of a church once, in a town far from here, where thirty years earlier there’d been a big argument over the use of the building, a group of people had left to worship in another part of town, and progressively the people who had left got old and died off, with just a small number of them remaining. But the rift hadn’t healed. And it was still a hurt that people didn’t want to talk about. They really needed to forgive one another, but they simply couldn’t do so.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu is a man who has dedicated much of his ministry to forgiveness. In South Africa after the end of apartheid, he chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which enabled an entire society of people to forgive those who had done unbelievable harm to them. Tutu has spoken and written at great length about the necessity and the power of forgiveness. He wrote that “without forgiveness, there can be no future for a relationship between individuals or within and between nations”.

We’ve all done so many things that we need to ask others to be forgiven, and many of us have had things done to us that are so hard to forgive. This is a subject that’s pretty difficult to confront. For some people, there are things that are too hard to forgive, or which take a very long time. It’s simply wrong to tell abuse victims, or families of those murdered, or people who have persecuted and hurt by institutions, that it’s their duty to forgive. One of the nasty and insidious ways that this passage has been used has to be try to force victims to come to terms with those who have hurt them, suggesting that otherwise they’re not fulfilling God’s will. Nobody should tell someone who’s been terribly wronged that they have to forgive.

And yet there are so many amazing stories of people who are willing to forgive those who have done them terrible harm. Desmond Tutu’s daughter, Mpho Tutu van Furth, herself an ordained priest, has written extensively of her experience in forgiving someone who murdered a person close to her. I heard her speak about this once, at the Greenbelt festival. She says that there is no one who cannot be forgiven – nobody is beyond forgiveness. Moreover, it is possible to forgive someone even if they show no remorse, and indeed by not forgiving someone you allow the one who injured you to dictate who you are. Forgiveness releases you to let go of the hurt and to move on. Or it might do so eventually.

|

| Image: The Other Press |

Nor is forgiveness just an individual thing. As a society we have committed so many acts that require forgiveness. The wealth of this nation for so many centuries was built on colonialism and on the slave trade, the exploitation of other people’s bodies to enrich people here. We can cast Edward Colston into Bristol Harbour, and quite right too, but our whole nation requires forgiveness.

Right now, we are damaging our planet on a level that is wholly unsustainable, through the profligacy of our lifestyle, with its pollution and its destruction of natural resources. We need to seek forgiveness from the earth, but just as much we need to seek forgiveness from future generations, those who are young right now like the school strikers, but also those generations as yet unborn whose lives may never have the same richness of the natural world that all of us here currently enjoy. This is an individual matter – we could all drive less, fly less, use less plastic, eat more sustainably and so on; but more so it’s a collective matter, and we need to change it collectively.

And I could go on about things we do, individually and collectively, that require forgiveness. I’m sure everyone here can think of many such things. But we have Jesus’ example to follow, in the forgiveness he gave to so many people through his teaching and through his life. The parable presents the negative side, of what happens if we don’t forgive. But Jesus offered forgiveness to so many, and continue to offer forgiveness to us today. God through Jesus forgives us of all our sins, however terrible; it’s simply asked of us to do likewise. In the Iona Community’s prayer of confession in their daily liturgy, the words of forgiveness read:

May God forgive you, Christ renew you, and the Spirit enable you to grow in love.

May it be so for all of us today, and may we find that forgiveness reflected in the way we forgive others. Amen.

Tuesday, 1 September 2020

Reflecting on twenty years at the Open University

|

| My office door for the past 20 years |

Teaching

|

| View from my office window in springtime |

Research

My research interests have also changed over time. By many academics' standards, my research career at the OU has been somewhat low-key, even weak. I've had no significant large-scale projects and no external grants (I've seldom seen the need, though occasionally I've applied for grants). I've published 3 books, 7 journal articles, 6 book chapters, and 7 good conference papers - not hugely many. But some of my research work I'm immensely proud of.

- Systems Thinkers: this is the biggest and best thing I've done. Back in 2002, Karen Shipp and I hatched a plan to take up one of the Systems Discipline's unfinished project, to write about the lives and work of the key people in systems thinking. After 2.5 years of a reading group with colleagues, and almost 5 years of intensive writing (and huge amounts of reading), this became our book Systems Thinkers (2009), which discusses 30 amazing people in loving detail through a series of 2500 word essays pinpointing their ideas and their lives accompanied by extracts from their work. Ten years later, Karen and I went through the 30 authors again, re-read our chapters, I read everything new I could find by or about our authors, and rewrote each chapter in the light of this, to produce our second edition (2020). I felt a real sense of passion for every single one of those 30 people as I wrote about them, a real urge to tell their story and link their ideas to the body of systems work; and I continue to be really pleased when I meet people who've found the book helpful. To date, chapters from the book have been downloaded more than 90,000 times.

- DTMD: my other big research work at the OU, this time with David Chapman. In 2007 we co-organised an internal workshop to look at the way different academic disciplines gave a prominent role to information as a concept, but treated it in very different ways. This led to an edited book, two more workshops in Milton Keynes but with an international reach and some excellent speakers; and then three more workshops at other people's conferences. Many of the events ran under the label 'DTMD', The Difference That Makes a Difference, from Gregory Bateson's celebrated definition of information. We brought together a lot of interesting people and really managed to contribute to the burgeoning field of information studies (and even had a research group for a time under the DTMD label). Latterly, with other OU colleagues, we moved the work in a more critical direction, looking at the social, political, racial and gender impact of information and refocusing it under the banner of 'critical information studies'.

Admin

The future

Friday, 3 July 2020

Sojourning in silence and systems

“For my journey was not solitary, but one undertaken with my friends as we moved towards each other and together travelled inwards.” – George Gorman, 1973 (Quaker Faith & Practice, 2.03)

A quarter-century at The Open University

Twenty-five years ago today, I walked into the Venables building at the Open University for the first time as a staff member, was greeted by...

-

The song "Jonah and the Whale" is much beloved at Sunday Schools . It's jolly but (like lots of Sunday School versions of the ...

-

[Sermon preached at Duston United Reformed Church, 30th March 2014, Mother's Day. Text: Luke 1:46-55 , The Magnificat. The sermon was im...

-

Sermon preached at Duston URC , 11 March 2018. Texts: Numbers 21:4-9 and John 3:14-21 . Image: imgflip.com A couple of months ago, my...