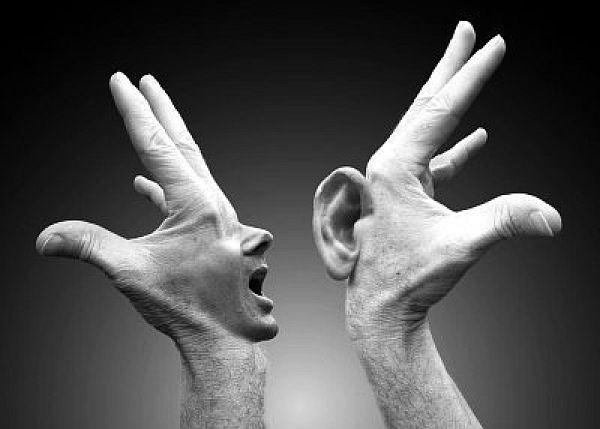

I hate you!

If he tells that story again, I shall hit him, I swear it.

If she says one more thing about my flowers, I’ll tell her what I think of her.

If he tells that story again, I shall hit him, I swear it.

If she says one more thing about my flowers, I’ll tell her what I think of her.

Conflict. It’s a part of any human community. John doesn’t like what Rosemary said, and he’s in a huff about it. John’s friend Bill gets drawn in, and Bill’s wife Jane, except that Rosemary’s sister Judith is already in an argument with Jane. And ten years later, the arguments remain, the hurts stay. The community is diminished, but nobody can quite address it.

And in churches, conflict can simmer and remain around for

many years, because people stay in the same churches for many years, even

sometimes generations. I was part of a church once where thirty years earlier

there’d been a big argument over the use of the building, a group of people had

left to worship in another part of town, and progressively the people who had

left got old and died off, with just a small number of them remaining. But the

rift hadn’t healed. And it was still a hurt that people didn’t want to talk

about. That was in a town far from here, but I know of similar stories of

churches in this area, where splits haven’t healed after years, or where people

carry on together in the same church community but are unreconciled to each

other.

I was angry with my friend;

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

However, the poem gets darker and darker. The unquenched

anger becomes something real and tangible. Eventually the poet kills his foe.

So what do we do about this kind of conflict? That’s the

subject of the reading from Matthew today. It’s not a cheery topic, not one

many of us would like to think about, but really important. I need to say

something directly before I continue. As someone who’s not been to this church

before, let alone preached in it, I want to emphasise that what I have to say

today is not loaded, it’s not based on particular conflicts between people

here. I’m sure there are some, but I don’t know about them. So rest assured

that any anecdotes aren’t aimed at specific people here – though that does mean

I might unintentionally hit on a raw nerve or two.

And Jesus presents us with a solution of sorts, though it’s

an odd kind of solution. The process Jesus outlines can sound incredibly harsh,

like a recipe for a disciplinary committee of the sort practised by our

Reformed forebears in places like Geneva and Edinburgh in the days when these were far from cosy places if you stepped out of line with the community. In fact it’s

such a difficult passage, and so oddly out of joint with Jesus’ style (not to

mention its use of the term ‘church’ when no such thing existed) that the great

Scottish biblical scholar William Barclay argued that it couldn’t possibly be

the authentic words of Jesus. And there’s the frankly quite odd statement that

if the offender should be treated like the pagans or tax collectors, who

elsewhere in the gospels Jesus is very welcoming towards. So is there really

anything to be taken from this? Well (deep breath), I do believe it’s a passage

that sits alongside Jesus’ other teaching, if you look at where he’s saying it.

First of all, the immediately preceding passage is Matthew’s

version of the parable of the lost sheep and the shepherd’s joy in finding it.

And then the passage is followed with two verses which aren’t linked with this passage

in the lectionary, but I thought were so helpful that we needed to hear them

today: Jesus’ statement to Peter that we should forgive something not just

seven times but seventy-seven times, or in some

versions seventy times seven times. That’s a lot of forgiveness. And it chimes

in with a saying of Jesus in the Sermon on Mount, that:

“if you are offering your gift at

the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against

you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to

them; then come and offer your gift.” (Matthew 5:23-24, NRSV)

So to me the passage needs to be seen in the context of

forgiveness, and of St Paul’s statement in our reading from Romans, saying “to

love is to obey the whole Law”.

If someone does wrong to you, you don’t kick back, you don’t

nurse a grudge. First thing, you go and talk to them. You need to say straight

out “you’ve hurt me, you’ve done me wrong”. That’s a shockingly difficult thing

in itself to do. Very often I don’t have the courage to do it myself if someone

has done me wrong. But it’s a necessary first step. And it acknowledges the

other person’s humanity, that they too are a child of God whatever wrong

they’ve done you. So there’s a lot of forgiveness needed in being willing to do

that. And it may be sufficient by itself.

But it may not be enough, and in that case we’re presented

with a couple of further steps: to bring along a couple of others to talk it

through with the wrong-doer, and then to take it to the whole community. That

last step is incredibly difficult – to tell everyone what has happened. And

this isn’t about gossiping, it’s about openly stating the issue. Imagine

raising a long-standing personal dispute as an item at the next church meeting.

It’s would be tough, unpleasant. But if it was done in the right way, in a

spirit of openness and loving forgiveness, and if the other person could hear

it in that spirit, and if the church could support you both through the process

– that could be the sort of thing that really heals wounds that fester over

decades within a community.

And if it still doesn’t work, Jesus advises, we are best to

openly acknowledge that the community is broken, to be public about it. It has

to be done in love and care. Religious communities have treated transgressors

really badly in the past, calling them excommunicated or expelled. But if we

can openly acknowledge that the person who has done wrong is looking in a

different direction from the rest of the community, perhaps with fault on all

sides, then that’s perhaps another way towards eventual healing. And it’s a way

to avoid blaming the victim, which I’ve not mentioned but can be a real risk in

some cases – where wrong is done to someone, but the community closes ranks to

support the wrongdoer and it’s the victim who is driven out of the community.

That’s happened far too often to women who have been raped, it’s happened far

too often to children who have been abused by people they trusted. What Jesus

is talking about is a way to love everyone and forgive everything, but to trust

the victim of wrong rather than blaming them.

Now I’m going to pass over the bits about permitting and prohibiting in heaven

and on earth, which

Now I’m going to pass over the bits about permitting and prohibiting in heaven

and on earth, which are a whole different sermon, because I want to talk about this wonderful statement, that “where two or three come together in my name, I am there with them”. There’s such a lot of richness in that statement. Does he mean us? This group of people gathered today in Jesus’ name? Yes he does. And he means every church everywhere worshipping today, wherever in the world in whatever ways. He promises us that he is there with us, holding our community together. And that brings me to discernment.

What the sequence of steps that Jesus describes reminds me of, is the process of discernment. I was

a Quaker for fifteen years, and Quakers have long talked about an individual

having a ‘concern’ – a matter that presses deeply on their heart. Often that’s

the way that real change begins, from one individual’s concern. Among Quakers,

it’s how the campaign against slavery began, how many peace-making efforts

began, and how their current witness for same-sex marriage equality began. If

such a concern is really strong, you might believe that it’s God telling you to

do something. But how do you know it’s from God? You pray about it

individually, deeply, at length. Then you bring together a small group to pray

together and to discern the leadings of the Holy Spirit on the topic. If that

group believes that this is something coming from God, you take it to the whole

church to seek their discernment. You might even go to another level within the

denomination to seek further discernment – in the URC that would be synods and

the general assembly. And what Jesus is saying here is a similar thing, but

about handling conflict.

If we want to restore community, if we want to restore

wholeness to our broken relationships, we have to seek the will of God

together, in wider and wider groups. We have to listen prayerfully to the still

small voice of the Spirit, and we have to be prepared to forgive each other and

to rejoice in the return of the lost one to our community.

We live in a world where the word community has become

grossly over-used. We hear talk of online communities, of communities based

around identity, communities based around lifestyle, even communities based

around what kind of gadgets you buy (the iPhone community or the Android

community). Yet we’re also in a world where community feels quite a long way

from many people’s lives. And we’re in a world where conflict and separation

are everywhere. Tensions may have reduced slightly in Ukraine, but they could

start up again any time. Syria is a constant sea of conflict and division,

likewise Israel and Palestine. So many of these sores are to do with ancient

hatreds that never healed, because nobody put in the work to make them heal.

What Jesus offers us here is a way of doing that, which if we practice it in

our own local hurts and conflicts just might offer a beacon of hope to a world

that is suffering so much from conflict.

One example of this working out in practice is the Truth and

Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, which practiced forgiveness on a

daily basis as it sought to bring out into the open the many terrible acts

committed during the apartheid years. Desmond Tutu, who chaired the commission,

says that “forgiving is not forgetting; it's actually remembering and not using

your right to hit back”. I heard his daughter Mpho Tutu, herself an Episcopal

priest in South Africa, speak last month at Greenbelt. She spoke very

powerfully about forgiveness. There is no one, she said, who cannot be forgiven

– nobody is beyond forgiveness. Moreover, it is possible to forgive someone

even if they show no remorse, and indeed by not

forgiving someone you allow the one who injured you to dictate who you are.

This fits so well with the compassionate as well as the uncompromising nature

of Jesus’ teaching.

Sticking with the wisdom found through injustice in southern

Africa as we come to an end, there’s a song from Zimbabwe, brought to this

country by the Iona Community, which is based on today’s passage. It runs:

If you believe and I believe

And we together pray

the Holy Spirit shall come down

and set God’s people free.

And set God’s people free, and set God’s people free,

The Holy Spirit shall come down and set God’s people free.

And we together pray

the Holy Spirit shall come down

and set God’s people free.

And set God’s people free, and set God’s people free,

The Holy Spirit shall come down and set God’s people free.

If we gather authentically in the name of Jesus, if we are

able to forgive one another, if we can rebuild relationships that are bruised

and battered – then the Holy Spirit will move among us, and God’s people will

be set free. Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment